A little while ago, I was awarded with a flash grant from Shuttleworth Foundation, thanks to Shuttleworth fellow Sean Bonner for his nomination. If you’re unfamiliar with Shuttleworth, it’s a neat foundation with a mission to create “an open knowledge society with limitless possibilities” through funding projects that embody the ethos of openness.

As a believer, thinker, and doer of open knowledge, Shuttleworth’s progressive message hits me close to home. This flash grant affirms my sharing of what I do while I am doing it, a work style that I’ve come to develop over the years. This openness challenges the competitive norms of this society, a world organized by individualism, meritocracy, and institutional forms of privatization and policy protectionism. In academia and the art/music world, I have learned and unlearned many lessons regarding the social consequences of knowledge production and dissemination.

To me, knowledge production has to be checked with social reality of what it does to our community. How do we talk about what we know? Who do we learn from? Who has access to this knowledge? Who is entitled to this knowledge? With whom should we share our learnings? Who benefits from this knowledge? Who is harmed by this knowledge? Which institutional and economic contexts support (or regulate) the production of knowledge? (I’ve talked about some of these concerns in the context of open access publishing and ethnomusicology previously.)

These are complex questions (and many folks including Deb Verhoeven, Kimberly Christen, and Michelle Kisliuk have spent lots of time thinking about this). The idea of openness itself is further complicated by the fact that there are multiple publics in the society, some weak, some strong. These questions form an ethical compass throughout all of my professional and creative endeavors. Because there are political and economical concerns tied to all knowledge production and dissemination, we should consider each context thoughtfully.

Last month, I completed a two-year fellowship. The ACLS Public Fellowship was a tremendous opportunity in which I learned my ways as a public-sector researcher and digital strategist during my time at the City of Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs. The Shuttleworth grant came at a good time to help support my post-fellowship work in a few community sound projects that I’ve put on the back burner. Specifically the grant is supporting my time and labor while I make progress to deepen my sound-based research and creative engagement to re-make the public sphere in Los Angeles, a city that I came to adore and care for.

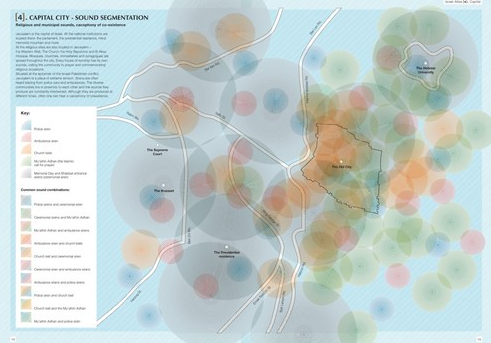

I’m making progress in LA Listens, a collaborative project that explores sounds of urban vibrancy in Los Angeles. In the last year, we developed a community-based methodology to engage with the social, ecological and experiential dimensions of the soundscape of city streets. Our methodology has contributed to the creative re-imagining of the acoustic public of particular locales and broader civic discussions about the role of sound in neighborhood changes and urban planning policy. Through a collaboration with MIT’s Community Innovators Lab (CoLab), We have shared research narratives including sound compositions based on our data have spurred a series of sound walks, location recordings, and sound-based provocations among urban planners and organizers in cities worldwide (summarized in this CityLab article by the Atlantic). I’m using my time to explore possible community partnerships and share our project reflection as blog posts and possibly a journal article. I’m also excited about funding a research internship for the project. Rounak Maiti, a former student from Occidental College, has joined the team to assist with field recording analysis and re-composition.

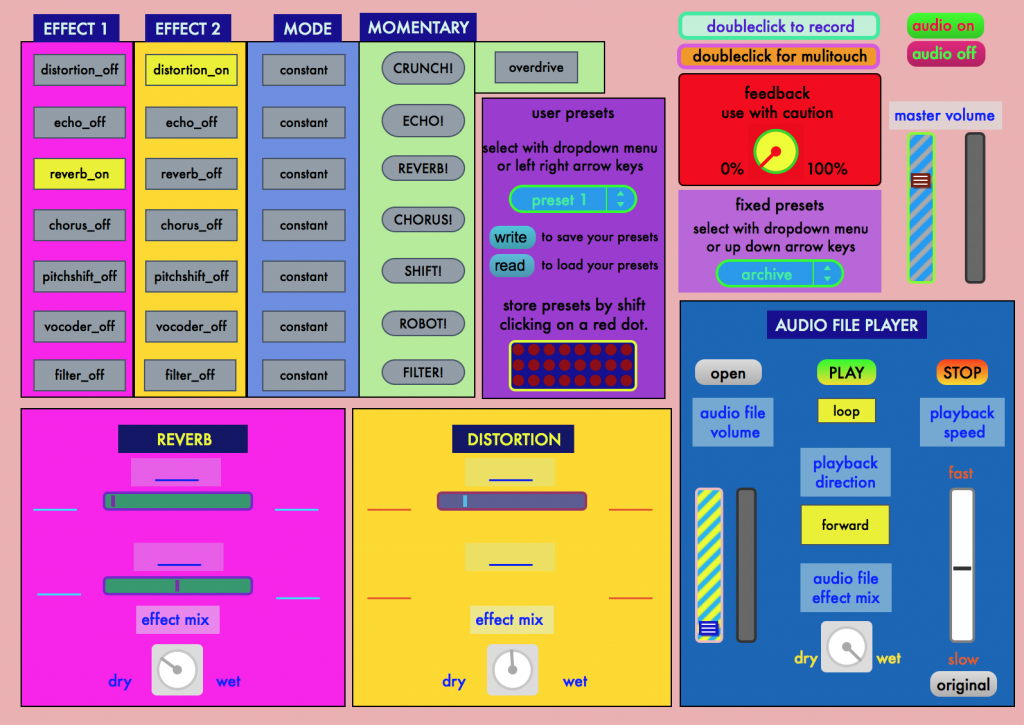

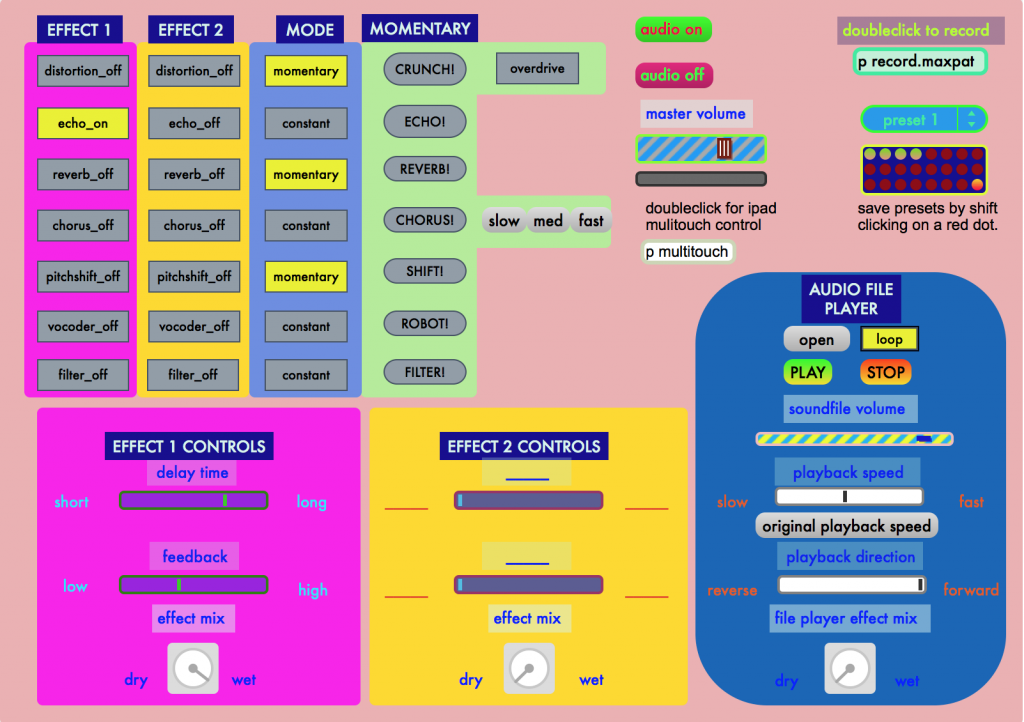

I have remobilized the Movable Parts team (a socially concerned maker collective) to produce a creative intervention regarding the collective mobility experience in LA. With a microgrant from Metro, we built a prototype for Movable Karaoke, a participatory multilingual system on a pedicab. During California Rideshare Week, we staged a series of karaoke events through the streets and at transit hubs such as metro stations, bus stops, sidewalk, parklets and plazas (documented on instagram). Residents and passersby in Koreatown, East Hollywood, Thai Town, Hollywood, Chinatown, and Pershing Square came to us, with adults sharing personally meaningful songs, children trotting along on the sidewalk and in the schoolyard. In the coming weeks, I plan to share my thoughts on rickshaw design along with some stories and experiences of collective mobility.

Working with fellow sound ethnomusicologist Yun Emily Wang, I’m co-designing a sound installation that will be included as a part of an exhibition at the upcoming Society of Ethnomuisoclogy meeting in Austin, Texas. This collaborative project will explore the meaning of “雜 (dza) through materializing the mixed, blended, miscellaneous, and insignificant odds and ends of sounds in Taiwan.” This coming Wednesday, I will be recording a live video set with my ghost pop band Bitter Party for the Ear Meal Webcast series. This performance will feature field recordings collected from recent trips to Taiwan, adding a new context to the band’s ethnographically driven song arrangement.

Labor and time are the building blocks in our creative economy. I give a shout out to Shuttleworth for playing a critical role in supporting me through this highly creative period, and for sustaining our broader creative ecology. Honored and thankful, I will continually share what I do in these exciting projects in the near future.

bio

bio