Since I work in the CDLR, I get to raise all kinds of wild questions that don’t fall into the purview of traditional, disciplinary bound scholarship. To prepare for my presentation at the Pop Conference (instituted by Experience Music Project in Seattle), this year combined with IASPM-US (International Association for the Study of Popular Music), I became preoccupied with the question: “How do I visualize a music analysis about space and place?”

My paper extends my dissertation work on The Kominas, a South Asian American punk band tied to the alternative Muslim subculture self-labeled as Taqwacore. In this paper, I chose to focus on the band’s music. Through a couple of song readings, I investigate the form and content of diasporic spaces as articulated by the band’s music. I argue that this unique geo-musical formation discursively moves seamlessly between a conventional notion of diaspora—migration of people away from an ancestral homeland—and a minority-centered, multi-diasporic space. Through a recent engagement with multimodal scholarship, I challenged myself to think beyond writing, a mode that conventionally represents academic work. I already use the concepts such as cartography and mapping as metaphors. Why should I limit the expression of my ideas to text only? Why not create a map of my music analysis especially since it’s about space and place?

Visualizing a musical analysis is nothing new. Music theorists have used music notations to represent sonic patterns key in their interpretation. More recently, theorists and information scientists used computational means to process sonic materials for patterns. Visualization became a way to explore patterns, bringing sounds into a (visual) domain that were previously inaccessible with the human senses.

My paper, however, does not engage with the use of the computational technologies to process sonic materials. It does something rather old-school. It simply draws several points on a map and then links them. It does not overlay demographic or musical data. It displays a couple of different geographical formations that illustrate the changing contour of a musical diaspora, a geographical space comprised of lyrical, sonic, and choreographic references. [I deployed Josh Kun’s concept of “audiotopia” to argue for the social and cultural effects of this geo-musical space.]

I began with a hand-drawn map. I used the Penultimate app on my iPad.

I quickly realized that my hand drawn diagram is not only messy but almost illegible. Through searching and playing, I settled with the web-based mapping program Scribble Maps to map this unique diasporic spaces. Using features such as vector graphics, media imports, and baselayer settings, I created a couple of maps that best approximate the geo-musical entities for which I argue in my analysis.

This map articulates The Kominas’ worldview. I positioned South Asia in a visually central spot, with the cultural region of Punjab and the city of Lahore highlighted. The song “Par Desi” articulates this geographical formation:

The song’s title explicitly figures the South Asian diaspora. Vocally and lyrically, the song evokes an ethnic and geographical quandary. The singer and bassist Basim’s voice shivers as he sings the chorus line, ‘In Lahore it’s raining water, in Boston it rains boots.’ The subject in the song defines his physical home in Boston, where he experienced an assault by skinhead punks. He sings, ‘They tried to stomp me out, but they only fueled the flame.’ The song narrates a history of migration and the emotions of displacement. It raises the questions, ‘Where do I point to blame, when men scatter like moths? /… how’d I get here, from a land with long monsoons?’

The song’s references to traditional bhangra, a dance music genre that originated in Punjab, further complicates this geo-musical formation. In my analysis, I argue that the band projects a transnational bhangra-punk sound:

[audio:http://beingwendyhsu.info/dissertation/ParDesi_2.mp3]An 8-second analog sample of live bhangra percussion comes into the musical present. Immediately, this sample transports me, the listener, away from the emotional space of the lament. Continuing the triplet pattern of the bhangra sample, the band transforms the bhangra rhythm into a collective punk-style chanting of ‘la-la-la’ in the final section of the song. This chant rejoices in the form of a Clash-like punk choir, roughly in unison with a distorted guitar.

This bhangra-punk aesthetic is projected from a South-Asian- or desi-identified ethnic space: imagined somewhere between Punjab, 1970s punk England, and present-day home in the northeastern United States. The Kominas, I contend, elides its physical home in Boston and the U.S.; at the same time, the band self-consciously embeds itself into historical punk England to reclaim a new musical home.

I discovered a different but related diasporic configuration in “Tunnnnnn.” This song articulates a minoritarian, multi-diasporic space.

The Kominas alludes to the original roots reggae version of the song (“Armagideon Time” Jamaican artist by Willi Williams). In doing so, the band resituates their version of the song into a Rastafari time-space. The Kominas locates its own battleground, while borrowing from the Rastafari visions of Armageddon.

[audio:http://beingwendyhsu.info/dissertation/Tunnnnnn_2.mp3]I hear The Kominas calling for its own ‘Armagideon,’ in the new lyrics written in Punjabi. According to Basim’s translation, the first verse states: ‘We will only drink that / That they are drinking in Iraq / We will only drink that / that they would drink in Karballah (sic).’ It is not a coincidence that both Iraq and Karbala are iconic battle sites both in the past and present. The War in Iraq after the events on September 11 has been a topical preoccupation by The Kominas since its first album (entitled Wild Nights in Guantanamo Bay). The band has made clear its stance of castigating the western world, in particular the United States, for waging a war motivated by Islamophobia, militarism, and imperialism. Following the Punjabi lyrics, Basim evokes the overthrow of 21st century Babylonians. In English, he sings the lines, ‘A lot of people won’t get justice tonight / A lot of people wont’ get no supper tonight / Just remember to / Kick it over / And praise Jehovah / And kick it out.’

The Kominas’ musical alliance with roots reggae, the music of those in Jamaica as well as the Jamaican immigrants, rewrites the history of the racial dynamics in 1960s and 1970s England. Challenging the history of “paki-bashing” in England, The Kominas’ music prominently figures the South Asian subjectivity. This musical geography has discursively reorganized the racial relations between blackness, whiteness, and Asianness. It also forges a musical alliance between a South Asian American band and the Afro-Caribbeans in Jamaica and the U.K..

In its overlays, these maps bring into relief various sites of geopolitics related to postcolonial struggles. This spatial articulation, I contend, is a minority-centered project of reterritorialization. It points away from the band’s physical home in the United States to re-focus on geographical sites symbolic of resistance. Its identification with loci of anti-white-supremacy and anti-imperialism, I argue, is a response to the post-9/11 social alienation and melancholia. Through the creative adaptations of Punjabi musical roots and transnational routes via the U.K., Jamaica, and Lahore, the band has built a psycho-social home in its music.

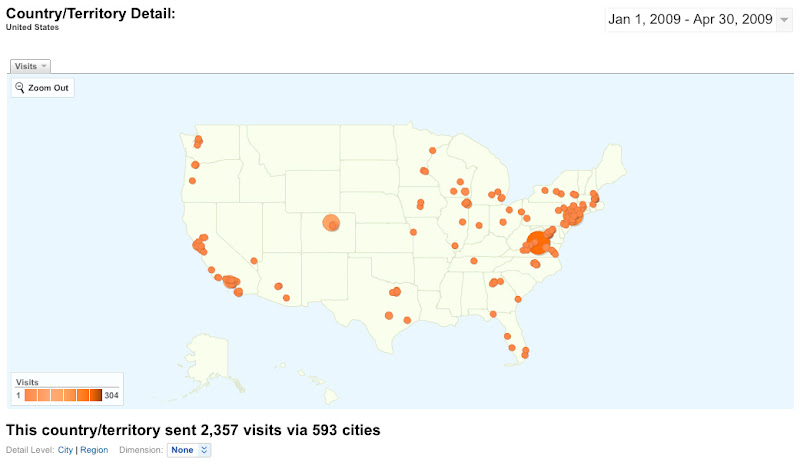

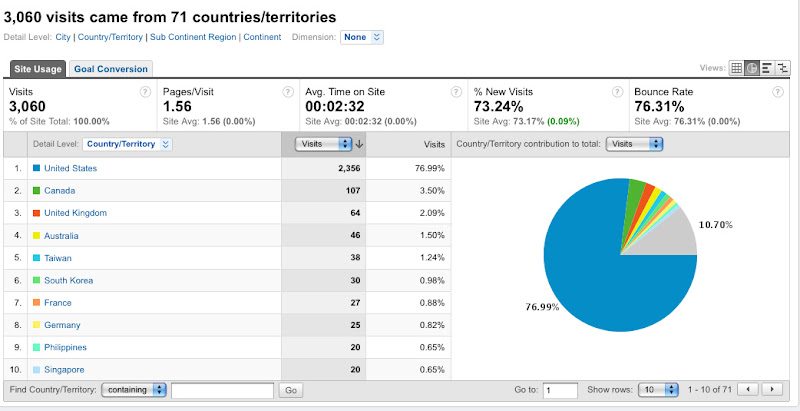

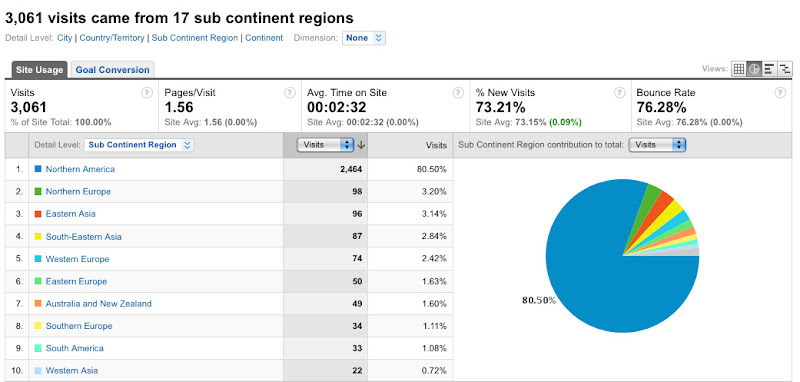

Coda: These two maps are extensions of my work at UVa’s Scholars’ Lab where I made a series of Myspace friendship distribution maps of a handful of bands (including The Kominas) featured in my dissertation. I’m happy that I’m in the position to use experimental and digital methods to further my explorations of the relationship between pop music and postcolonial geography. This cluster of ideas and modes of inquiry truly excites me.

bio

bio