Last week, we hosted the first of our Studio Sessions in the CDLR. Harnessing my interest in popular music, as a scholar and a performer, I thought that I would experiment with multi-track audio production using the iPad. I was inspired by all the iPad bands that are burgeoning on Youtube and especially empowered by to see that this emerging genre is heavily populated by women in Asia.

From my days of playing experimental music, I found that libraries are not only a day-job shelter for some of the most innovative experimental artists that I know (Khate, Jimmy Ghapherhy, Sharon Cheslow). Created for people to treat information and knowledge with care, libraries make a fantastic space for experimenting with the modes of production of cultural and intellectual content.

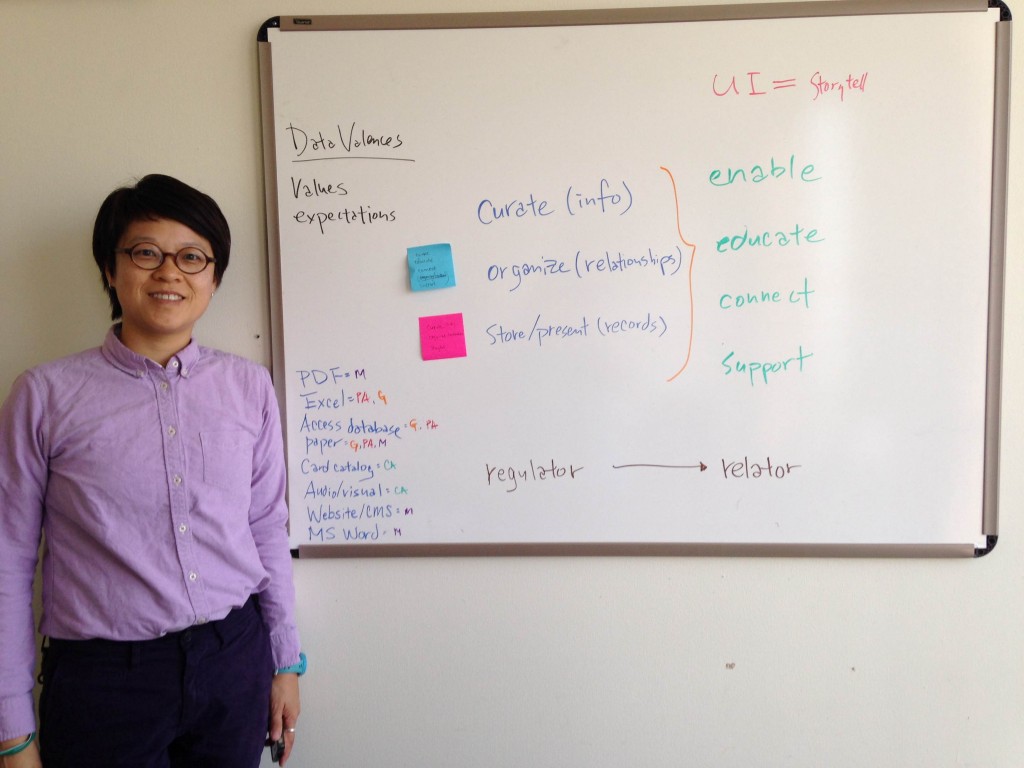

At the event, I transformed the CDLR into a mobile music recording studio. I moved some furniture out of the way. Using table cocktail tables, I set up multiple stations to track various instruments: electric guitar/bass, MIDI controller, USB voice/acoustic instrument. The guitar interface made by Apogee Jam makes it possible to plug an electric guitar directly into the iPad to control the built-in digital amp models. Via an Apple Camera Connection Kit, the MIDI controller and the USB microphones were connected to the iPad. The MIDI controller enabled the user to control and record various software instruments (fancy keyboard sounds like vintage organs and synths). I set up a “vocal booth” using the USB mic in the small compartment inside the CDLR to record sounds that travel through the air. We did a couple of close mic experiments. Tom Burkdall of the Center for Academic Excellence recorded his a capella version of an Irish pub song. Throughout the course of the session, Utsav, a student participant, recorded a cover of “Hey Soul Sister” that features his baritone ukulele.

The GarageBand Studio Session was the first event of CDLR’s “Year of Collective Learning through Critical Making + Code.” We designed this series with the intention to encourage the Oxy community to experiment with technology in ways that go beyond the end-user / consumer roles. I can say with confidence that the event achieved the goal of critical learning through making.

Let me illustrate this point by narrating my interactions with Amanuel, a first-year student at Oxy. He told me that he has had no experience in songwriting and audio production. He indicated that he didn’t feel comfortable starting out the session by playing with an instrument. I thought this would be a great opportunity to play with the sampler feature in the GarageBand app, which allowed the musically uninitiated to play with samples of sounds that are programmed to fit the (western) scalar tonal system. He quickly migrated into the Smart Percussion and Smart Keyboard. In a couple of hours, Amanuel made complex patterns of instrumental sounds.

[soundcloud url=”http://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/38388472″ params=”auto_play=false&show_artwork=false&color=ff7700″ width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

While I was thrilled with Amanuel’s progress, he appeared to be discontent with his work. He told me that his music doesn’t sound right. After probing him, he revealed that his music doesn’t sound like Kanye West’s music. I recommended for him to sit down and study Kanye West’s music. We discussed principles and elements of pop song form. I left him to his own device to do some close listening. Without prompting him, I saw that he listened closely and jotted down notes about the song’s sections and structure. A little later, he tapped on my shoulder, “yo, this song sounds like really simple. The form is simple and is built on a few simple tracks.”

I said, “well, you’re totally right. Kanye West’s music is pretty simple in terms of its form. If you cam either be like him, make simple forms with your songs, or you can go with a form more complex than Kanye’s.” He seemed surprised by my claim.

He scratched his head and then went back to listen more examples of his favorite music. He played for me his recent favorite song “Tommy Chong” by the Blue Scholars as an example of a single-track keyboard introduction. Shaking his head, he indicated that he wished he could write a cool keyboard melody like the Blue Scholars. I said to him, “well, it’s not as hard as you think. This keyboard riff is in a pentatonic minor scale.” Then I showed him how to limit the keys on the GarageBand keyboard to only the tones in the specific preset scale. Bang! He instantly heard the difference between a pentatonic minor scale and a major scale by interacting with the keyboard algorithms in the app. [And if this were my Race and Gender in Popular Music class, then I would go on to the talk about the song’s keyboard riff in light of the group’s Asian American identities and explain the semantic significance of the pentatonic scale in the representations of the east in western music and media. I may even throw out Orientalism as a theory to contextualize this musical sound.]

Contrary to how I usually teach the concept of scale, via musical notations drawn on a chalkboard, coupled with a demo on a piano, the method of learning music through making a song on a tablet seems incredibly efficient and effective. The immersive practice of constructing a song, enabled by the tactile and visual components of the GarageBand app seems to me a more holistic approach to learning musical principles. By piecing together elements like tone, timbre, scale, harmony, section, melody, and rhythm for the task of building a song, students can learn the relationship among these musical components through a series of sonic and visual exercise, trials & errors. Not only that, this process also demystifies songwriting and could help students gain a critical perspective on the “artistry” of popular music.

I have talked about the cycle of learning, making, and then back to learning—as illustrated in my title “making songs to learn about songs.” From here, I’m interested to see what other music scholars and teachers have said about learning through making, in particular mobile music-making as a pedagogical practice. Wayne Marshall has theorized on mashup as “musically expressed ideas about music.” While he has mostly suggested mashup as a scholarly practice to articulate music analysis, I’d be curious to see how he develop his theory to include it as pedagogical practice for students to explore in a classroom. Ultimately, I want to produce a mixtape containing critical songs about songs made by students. Maybe next spring.

Listen to our set of tracks from our GarageBand Studio Session [FYI: track 3 “Our Desert Sounds a Little Different” is by yours truly; track 2 “Like Sardine in the CDLR” is by Carey Sargent]:

[soundcloud url=”http://api.soundcloud.com/playlists/1694463″ params=”auto_play=false&show_artwork=true&color=ff7700″ width=”100%” height=”450″ iframe=”true” /]

…

Before I wrap up this post, I want to riff on one corollary related to gender [that is perhaps the beginning of another central point about critical making]. There were no female participants at the event, except for one student’s friend who was invited to come into the studio to record a vocal harmony part. This is especially surprising because among the four adults staffing the event, three were women. And I, as someone who was visibly female, was clearly running the show. Is a recording studio a conventionally masculine space? Does the name GarageBand imply an old boy network? Yes and yes. At times, the CDLR felt like a music instrument store where male student participants took up substantial sonic space, noodling loudly on an electric guitar. And no one, including me, stopped them. I was bothered by it, but I didn’t want to impede their explorations by “being anal.” It felt disruptive to me, but I wasn’t sure how much it was affecting the sonic space of the other participants in the room. I was timid, as other female participants would’ve felt in that space.

I should consider this observation within the current discussion on the gender issues in the DH making/coding community instigated most recently by Miriam Posner. I agree with Miriam and those who spoke up this week against a kind of (gender/color) blind liberalism in the DH making/coding community. The “yourself” in the DIY communities isn’t necessarily white boys, but it could be in many instances. But we should probably do what we can make sure not only that there’s room for others, but that these others are sufficiently empowered in ways that they desire to be. We will have to introduce e-textile and softwear at the future iterations of our studio session. And/or we may just institute a Riot Grrrl studio series or a Grrrl(THAT)Camp.

bio

bio