Cross-posting from the MovableParts blog — I’m writing to introduce a new series that explores the intersection between my research on nakashi street music-culture and contribution to the concept design for Movable Parts.

I revisited our project concept as I was preparing for our talk in the Arts and Electronics for Designers class at UCLA Extension. The latest version of my vision for Movable Parts is: to deploy a sound/place-making paradigm transplanted from Taiwan in order to spark bustling experiences in Los Angeles. In this post, I will elaborate on the meaning and practice of the nakashi (那卡西) street music-culture and connect to it our current creative engagement in and with Los Angeles. This is an attempt to bridge my research on Taiwanese and more broadly global practices and platforms of mobile performance with the Movable Parts design and build project.

What is Nakashi?

Nakashi is an itinerant performance practice in Taiwan. Brought over from Japan during the Japanese Occupation Era, Nakashi in its original Japanese is “Nagashi” (流し), meaning “flow.” Flow refers to a flexible mode of performance that has spatial and social connotations. Nakashi musicians use sounding objects such as instruments and loudspeakers to create ad hoc, mobile stages. Traditionally, using acoustic guitar and accordion, Nakashi musicians traveled on foot to perform popular songs of their time in tea parlors and hot springs resorts. Over time, nakashi performers innovate their practices by constructing stages on pickup trucks and farm tools to set up performances in the streets and public areas such as temple plazas. Equipping these mobile stages with loudspeakers, they turn toward the streets and public spaces as their stage and spontaneously attract audiences. The photo below is an example of a performance troupe that traveled on a truck bed while disseminating sounds of their performance in the streets. Notice the loudspeaker that’s mounted on top of the mobile mini shrine.

The sound truck is a pervasive model in the nakashi street culture in Taiwan. It has become a platform for vendors to generate mobile and spatially flexible audiences and clientele. The practice of mounting speakers on a moving vehicle is common among street vendors (ex. “dirt-roasted chicken” 土窯雞, freelance recyclers, and campaign trucks). These moving sound trucks make up a distinctively Taiwanese soundscape. Representing the voice of a migrating urban underclass, sound trucks constitute the gritty sound of the loudspeaker culture that is increasingly disciplined by informal and formal noise control in urban Taiwan.

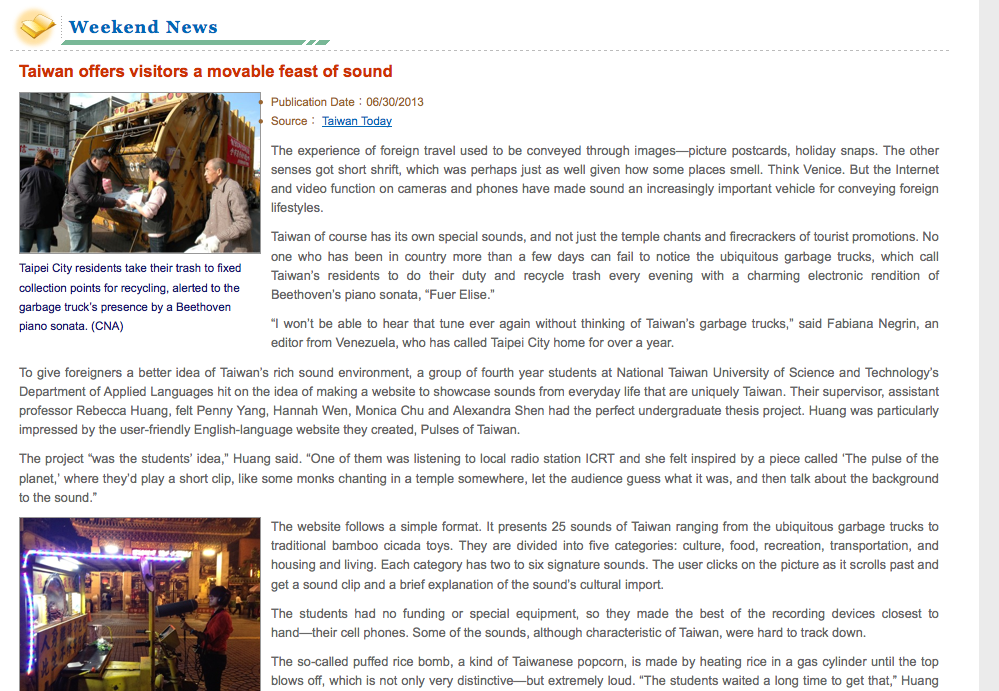

On my last field trip in Taipei, I encountered a sound truck that in many ways represents the Nakashi performance platform and sensibility. Parked across from Lungshan Temple, the largest temple in Taipei in Mejia (Monga) district, the Exhortation Touring Tricycle is a mobile sounding platform that functions as a store that sells religious and folk recordings to passersby. The multi-colored LEDs, calligraphy writings, and custom-built shelving add to the down-home, ostentatious sensibility of nakashi. Encased within hand-built cabinets that are mounted in the back of the truck, the speakers broadcast popular Taiwanese tunes mixed with didactic music that teaches taoist morality and buddhist cosmology. Mobility serves as a dissemination tool. Sounds of exhortation move while extending its messages through the streets.

On sound trucks or in stationary performances, amplification is a critical element in nakashi performances. Stationary nakashi performances typically take place in public spaces such as parks and metro stations. They are all unabashedly powered by diesel generators.

On my trip, I stumbled upon a performance in a park across the street from Lungshan Temple. Sound of amplification becomes aestheticized and is often heightened in a nakashi performance. In addition to its utility, the generator becomes an invisible sonic constituent that underlies all of these performances. In the video below, listen to the sound of the generator that powers the sound amplification. An overdriven amplified sound results a distorted, gritty, and lo-fi timbre. With an added effect of reverberation (in the vocals usually), nakashi amplification make up a uniquely textured sound-space.

What nakashi provides us is a mobile performance paradigm that intersects sound and place making through the use of low-resource technology. The constituents of both sound and place are inseparable. They make up the utilitarian and aesthetic core of the nakashi culture. Sound constitutes the social experience of a place; and vice versa. Sound plays a central role in creating not just any kind of space, but a bustling place where people congregate and form transient but meaningful micro-communities.

Sound/Place-Making for a Bustling LA

So how does this streetside practice in Taiwan relate to Movable Parts, a project based in Los Angeles? LA has an unusual history as a metropolis without distinctive sites of urban density. A city built for highways and suburbs, its decentralized structure makes location-based vibrancy a scarcity. At my day job where I work as an Arts Manager with the City of Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs, we routinely come up against the city’s geography as physical and social barriers when we administer arts and cultural resources.

To mitigate the geographical and social fracturing that marks the LA experience, we at Movable Parts thought to make human-scale creative systems. Developing systems that generate a creative friction against the urban sprawl, coupled with event design and community collaboration, we spark place-based social interactions.

As a sound ethnographer of Taiwan, I’m interested in recreating a particular notion of bustling — renal 熱鬧. Re means “heat” (often used to describe the heated, hyper state of human presence) and nao means “loud.” Together, with an abundance of human and sonic energy, renao represents a specific kind of vibrancy that is lacking in LA. I’d like to think that what we’re doing is to create a platform to ignite an abundance of energy in a city that lacks these elements of social life, particularly in the public; or otherwise, to amplify the less legible social energy in an a city with compartmentalized and hard-to-access publics.

In the video, LISTEN to the embeddedness of conversations, scooter sounds, and lo-fi music blasting from the Exhortation Tricycle’s homemade speaker cabinets. Pay attention to the dynamic between sound and place-making in this scenario. This immersive multilayered sound environment is culturally desirable in Taiwan. A sonic and spatial experience at once, this recording comes close to embody the meaning of renao, a place-based abundance of social energy.

On a slow sound walk through the Menjia Night Market, I captured layers of nightlife cacophony saturating the bustling “Old Taipei.” Sound sources in this location recording include pervasive pinball arcade, children’s bantering over games, passing scooters, and pre-recorded techno music and sales messages piped in through lo-fi loudspeakers mounted discreetly in the semi-outdoor vendor’s booths. I love how one could identify the human, mediated, and (analog) machine elements of these sound sources in the recording. This variegated texture signifies social multiplicity and technological vicissitudes as, I would argue, key meanings of renao.

Provoking a Bustling Downtown at CicLAvia

For the first iteration of our project, we designed and built a pedal-powered generator that provides electricity for a set of PA speakers. Each piece of the system — the battery and the hub motors — could be transported via bicycles. By bringing people together to pedal in order to generate electricity (I blogged about the social meaning of power generation earlier), we create a Movable Party. Resonating with the classic nakashi model of generator-powered performances, the Movable Party is an outcome of our engagement with sound and place making through a combination of low-tech and high-tech modes of practices.

I captured this video at our performance at Ciclavia last October. Teaming up with a group called DanceLAvia, we set up our bicycle generator in front of Grand Park in downtown LA to encourage CicLAvia participants to slow down for a dismount point. There we spontaneously recruited passersby as participants including the young participants shown in the video. On that day, we made progress toward our goal of making a bustling micro-community in LA.

Does this embody the Taiwanese notion of bustling — renao? Who could we mobilize individuals to participate in the making of bustling in LA? What would renao in Los Angeles sound and feel like? Does it depend on the neighborhood and other social and geographical factors? I hope that by asking these questions, we will continue to productively experiment with this wild transpacific sound and place-making paradigm.

bio

bio