An article about sounds in Taiwan came out in Taiwan Today, an online news digest in English published by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Republic of China (the official, government-sanctioned name of Taiwan). The author of the article Steve Hands contacted me a few weeks ago asking me a set of interview questions regarding my recent field (recording) trip to Taipei. My answers reflect a critical angle, particular of the government; but only parts of my personal narrative and ethnographic research rendered as apolitical were included in the final version of this tourist-friendly article. I’m happy to engage in a conversation about Taiwan’s unique soundscape. But I thought that I would provide my complete answers to his interview questions in this post. With context, I hope to nudge this dialog to move alongside some of the social and political issues at stake.

Taiwan Today: What is your favorite Taiwan sound?

Me: The street vendors in Taiwan use the available technology, often low-resource materials like a megaphone or a car stereo system hooked up to a loudspeaker, to make audible their presence and whatever products or services they’re selling. Among these sound street vendors, I am most fascinated by the sound of the mobile street vendors. An ingenious setup, street vendors can create a space of their own through sound, using sound to form a sonic public with invisible and moving boundaries. This sonic and mobile structure covers much more space than a stationary vending setup, because sounds travel through air and in space much farther than visual and stationary objects.I have very fond memories of hearing the sound of truck vendors that sell clay-roasted ducks around my neighborhood. There are less motorized versions like the sweet potato (Yam) vendor who uses a rattle to attract people. Specifically I went around Taipei looking for recyclers who peddle through the city on a tricycle (sometimes motorized) on this trip. These recyclers use a sound system to project messages to inform local residents of their service to pick up recyclable goods like bottles and jars, scraps of paper, metal and plastic, and sometimes electronics.

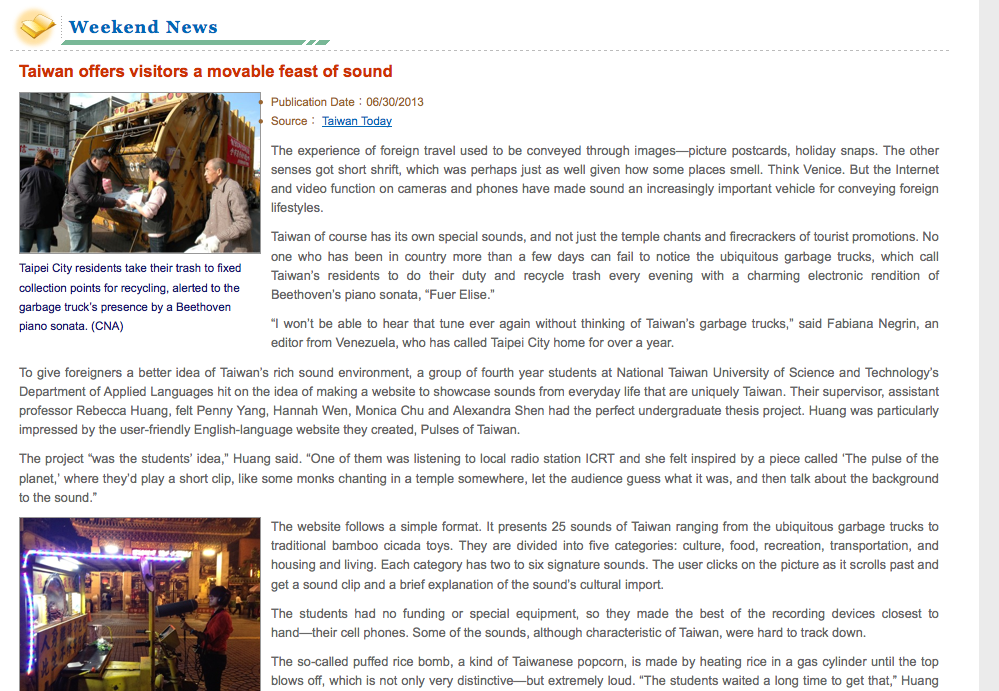

The city-sanctioned trash trucks have followed this practice to make audible their pickup service, except other than using a person’s voice pre-recorded onto tape or CD, the city trash pickup sounds more institutionalized with its pre-programmed MIDI of classical music (Beethoven’s Fur Elise). The choice of “classy” sound, I think, is intended to draw distinctions from other unsanctioned street vendors. These sound trucks are also used outside of commercial contexts. I have seen versions of musical trucks (a wide variety including nakashi trucks and Electric Flower Truck 電子花車), and recorded one — the Exhortation Tricycle that Tours Taiwan — that sits in front the Longshan Temple on this trip. I have recorded some political campaign trucks that are set up similarly, using loudspeakers to project live and recorded campaign related messages.

Unfortunately, these mobile street vendors rarely broadcast sounds into the streets as they travel. The sonic publics that they create are disappearing. I have a feeling that their vanishing is a result of the noise ordinance and regulations due to the interest of developers and private-public partnerships, and and other gentrification related issues.

Taiwan Today: At one point you mentioned the Chinese concept of renao. Could you elaborate on this a little? Is this a big difference between East and West, a love versus a dislike of noise? What are the best places for a tourist to experience Taiwan’s renao?

Me: Renao is a rich concept and it’s more complex in practice. “Re” 熱 refers to heat, or a heated state of being and sociality. Nao 鬧 refers a space or an event that is marked by noisiness, loudness, and movement. Together, renao as a term refers to a hyper state of social energy that is expressed through movement. The closest concept to renao in the Anglophone world is bustling. Bustling suggests a social state that marked by people’s movement through space.

What marks renao as a unique concept is that sound is a core expression and constitution of its physical manifestation. Richness in sound and movement makes up the transient experience of a “heated” sociality. Traditionally, one could experience renao or ken renao (看熱鬧) in front of the temple of the town or village, where there is the most foot traffic. It is also there where street vendors, musicians, and beggars gather forming the infrastructure for an informal local economy.

Nowadays, renao is experienced in public spaces like parks, markets (day market or night market), and occasionally in the streets during temple festivals and political campagins. Definitions of noise are socially constructed. What’s considered to the loud and noisy in one cultural context can be constitute the everyday life in another culture. (My friend Yun Emily Wang has written a MA thesis about the meaning of sound in Taipei. In it, she draws a distinction between renao and chaonao 吵鬧 in the way people use these terms to make social boundaries.) My sense is that renao as a practice is being challenged at the moment. Renao has been linked with the lowerclass. With the shrinkage of public spaces, and the government’s efforts behind cleaning up the streets (in corroboration with private entities like developers), renao has begun to decay in sound and in practice.

bio

bio

One comment