My dissertation project investigates the musical and social life of current independent rock musicians of Asian descent. This research looks at the music, interviews, and social interactions of these musicians. How do I do this?

Prior to working with UVa’s Scholars Lab, my method of field research had been participant observation: attending concerts, doing formal and informal interviews, interacting with the musicians’ friends and fans, listening to their recorded music, organizing local performances on their tours…an immersion in these musicians’ multi-faceted musical life. As soon as I began my field research, I discovered that the notion of “the field” has changed because of the prevalent usage of digital social media among the musicians of my study. The Internet, is no longer just a means of communication between me and my informants. Digital social media make up an important site of social interactions and creative expressions. Not only that, it is the key to social networking and community building for these musicians. Thus the “field” of my investigation came to include the digital social terrain that I navigate within the scope of dissertation research.

This post focuses on the map of one of the bands that I study: The Kominas. The Kominas is a South Asian American punk band that spawned in Boston, now based in Philadelphia. Recombining sounds from the Boston ska-and-crust-punk scene with 1970s Bollywood movies and Bhangra music from their parents’ dusty tape collection, The Kominas evokes a radically transnational sonic landscape. [Example “Par Desi”] Since 2006, the band has been vigorously creating a translocal social terrain via face-to-face interactions through touring and online social networking. The Kominas’ do-it-yourself network is comprised of Muslim-, South-Asian-identified, and other taqwacore-inspired musicians, listeners, artists, filmmakers, and bloggers.

In this post, I ask: What does The Kominas’ “digital diaspora” look like geographically and spatially? First, I will describe the digital methods I used to map this community.

Digital Methods – Web-scraping and Visualization

To create such a map, I designed and executed out a two-phase method. Phase 1 is web-scraping, the process of mining data from the Internet. This process entails first, locating a source of useful geographic data, and then harvesting this information programmatically. I was interested in two sets of data, specifically: the physical location of the band’s performance tours; and the self-reported (physical) location of the friends in an online community. The first set of data, regarding performance locations, was found on The Kominas’ official website. The information regarding friend locations was found in its most complete form on the social networking site Myspace.

To extract and process these data sets, with the help of Joe Gilbert, I wrote a program using Ruby to parse out the relevant information in the source code of the profile pages of The Kominas’ Myspace friends. The Kominas [as of April 2010] had close to 3,000 friends on Myspace. These are all Myspace users who have requested to become friends with The Kominas, or vice versa. Using Mechanize, a Ruby gem, the program extracted all the geographically related text from the Myspace profile pages of 2,867 friends. Using the Geokit, a ruby gem that implements the Google Geocoder, the program translated this information into a set of spatial coordinates, specifically, latitude and longitude.

Phase 2 – geospatial visualization – is the process of turning the harvested data into a meaningful visualization. Using OpenLayers, an open-source mapping program, I created a dynamic map containing all the points of the physical locations of the band’s Myspace friends and performance tours. To contextualize the reading of the physical points, I added various map layers. For example, I added a Google street map layer to label the visualization with the proper name of countries and cities. The rest of my efforts were spent to refine the map, to make it readable and meaningful.

The Kominas’ Digital Diaspora Map: GO!

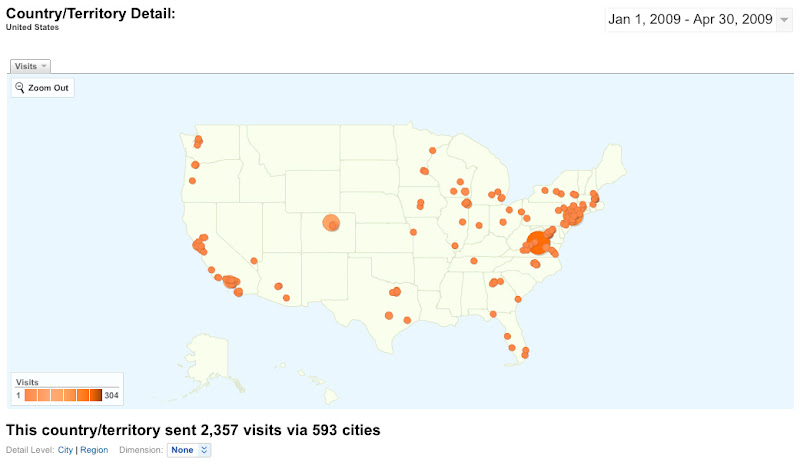

To interact with the map, click on the above image. This screenshot shows the global distribution of The Kominas’ Myspace friends. The reddish pink clusters represent the friend density in the respective locales. The size of the cluster is an approximate representation of the number of friends in one location.

A baselayer of the world’s regions – marked by various shades of green in the background – helps contextualize the friend distribution across continental boundaries. At a macro level, this map articulates a radically transnational and inter-continental distribution of friends. Areas of high friend density include: North America, Europe, and Asia. The story of translocality becomes more complex as we zoom in on the map to get more geographic detail. In my dissertation, combining maps, music analysis, and interviews, I examine how the members of The Kominas position themselves geographically and ethnically vis a vis this vastly transnational world.

Questions and Concerns

These maps tell a story, a particular kind of story that situates a humanist study of a music-culture within a particular geographic context. In the context of my dissertation, these maps add a spatial texture to the understanding of the translocal social terrain of a U.S.-based musicians of Asian descent. And the visualization process helps me to analyze the musicians’ questioning of their sense of ethnic and national belonging and to situate the ethnographic details of my 24-month field research within a global context.

Here are some more general questions and concerns that I’ve encountered in creating and using these dynamic maps. To express density using a clustering pattern, I used an algorithm that balances point density and readability, so that the contrast between the smallest and the largest clusters is adjusted. In this case, a single-point cluster can be seen and the largest concentration of the friends of the northeast of the United States doesn’t dominate the entire map. This presents the question, am I interested in representing the mathematical reality of this friend community? Or is there some part of the story that I was more interested in telling? Which level of detail is most useful?

I’ve discovered that these maps do not provide any answers to my research questions. They, in fact, present an interpreted reality that generate further useful questions. A map is certainly not a dissertation chapter; but it provides a spatial and geographical context for the musical and social experiences of the musicians in my study.

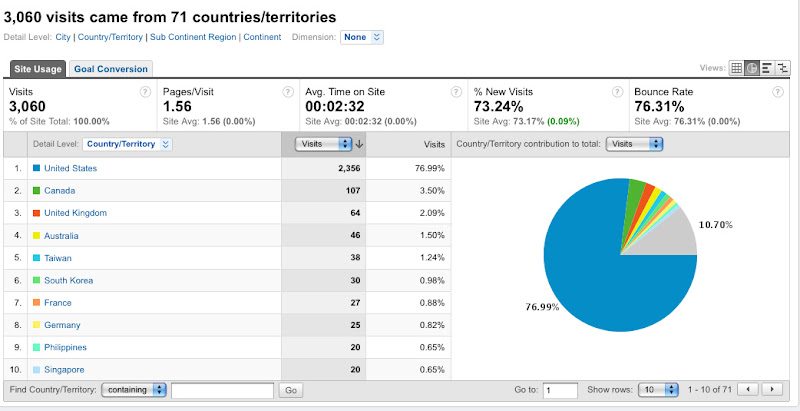

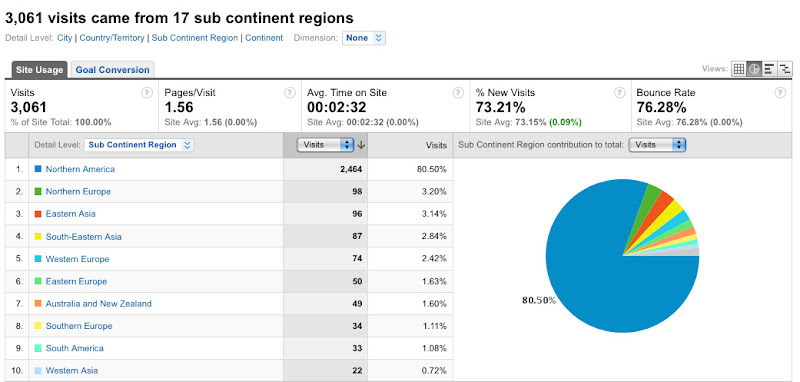

How I use these maps, of course, depends on the narrative that I want to tell. At a very macro, global level, zoomed all the way out, these maps can look very similar across bands: with large clusters in the North American region, some clustering in Europe, and some but less in other regions of the world. NOT SO INTERESTING…

Of interest to me, in my dissertation, are the patterns of the band’s transnational connections to musicians and fans in Asia. What is the band’s friend distribution in Asia? Is it useful to compare the Asia-based friend distribution across band? I have shown two screenshots of two bands’ friend distribution in Asia. On the top is The Kominas. On the bottom is Kite Operations, a New-York-based noise rock band.

This comparison presents interesting results: These two maps show that The Kominas, a South Asian American punk band has created a social geography much more concentrated in South and Southeast Asia; whereas Kite Operations, with 3/4 of the members being of Korean descent, has stronger friend presence in East Asia, specifically in South Korea. The difference in friend distribution shown by these images can provide a sketch for illustrating a different “Asia” as created through the cultural practice of “friending” on Myspace by American artists of Asian descent.

Combining Digital Methods with “Conventional Methods”

These digital methods seem to have an orthogonal relation to more conventional ethnographic methods. Until these new digital methods become accepted in ethnomusicology and cultural anthropology, I must find a way to integrate the new with the old. [Yes, I have thought-experimented with a set of digitally engaged ethnographic methods.] Here are some ideas for this integration:

- Showing the map to the musician-informants: Asking them if they are surprised by the results of my study. Asking them questions about how they feel about these places in the world? Personal or musical connections to these places?

- Toward a Geospatial Music Analysis: Many musicians that I study are pre-occupied with geography. In their lyrics, they often discuss being trapped or living in a limbo between two worlds. They talk about their feelings regarding certain meaningful place and space in their music. It’d be potentially fruitful to juxtapose the musical and social geographies of a single band.

- Mapping genre/sonic differences: Here I suggest the possibility of incorporating sonic qualities such as tempo, timbre, volume, studio effects, and language/dialect into geospatial information technology and system. Such a tool would be immensely powerful for the study of the world’s music-cultures at the local and global level. For example, the World Musical Map project by Ozan Aksoy based at the New Media Lab at the Graduate Center of CUNY explores the rupture between audio boundaries and actual national borders. Another example is Lee Byron’s visualization of the listening history on Last.FM.

Here’s my attempt to start a digital (ethno)musicology. Are there any other takers?

The Kominas’ Digital Diaspora Map: It’s Your Turn. GO!

Tips:

- Double-click to zoom in on the map

- Upper-left: turn on/off various layers: Google Street/Satellite; world’s regions; Muslim-majority countries; clusters (friend density); friends (individual points); gigs.

- Scroll on the map by clicking + holding + moving the cursor

bio

bio